Jump to . . .Step by Step | OS Map | Downloads | Gallery | Fly through

In a recent group trip to Kirkby Stephen, we enjoyed a great walk along a disused railway line. A quick glance at the map shows that the fantastic Smardale viaduct which we visit today is not far from there – and unsurprisingly it’s on the same disused line, so if you wanted to join the two routes you could.

The viaduct alone is worth the trip, but this walk offers much more: Great views back to the Howgills and Wild Boar Fell, industrial archaeology, wildflowers, lizards, and free parking within walking distance of two award winning pubs.

Much of the route is on accessible paths so although it’s close to our 12km threshold for an easy walk, this one is well worth considering for those wanting a gentler stroll.

- Total distance 11.1 km (6.9 miles)

- Total ascent 199 m

- Easy walk

Step-by-Step

We start at Ravenstonedale, a quite village with ample roadside parking. Take the M6 north to the Tebay exit and then take the A685 toward Brough. Continue through Newbiggin-on-Lune, which we walk through later in the day, and then ½ mile later look for the sign to Ravenstonedale on the right. Follow the road down into the village and park at the car park near the church, or at the roadside toward the Kings Head.

If you are using Satnav to get there, then the address for the Kings Head is Riverside, Ravenstonedale, Kirkby Stephen CA17 4NH, or the What-3-Words tag is stored.lashed.slant, corresponding to the OS grid reference NY72130426. Please take care if you park near the church to look for signage indicating services – blocking the parking at these times would be antisocial.

Assuming you have parked on the road down to the Kings Head, start by walking back uphill toward the church. On the right you might notice the rather imposing entrance to Elm Lodge. This was once a residence for a family, that by all accounts still lives in the village, but is now operated as an upmarket holiday residence. So, if you have a large family group and deep pockets this one could be for you.

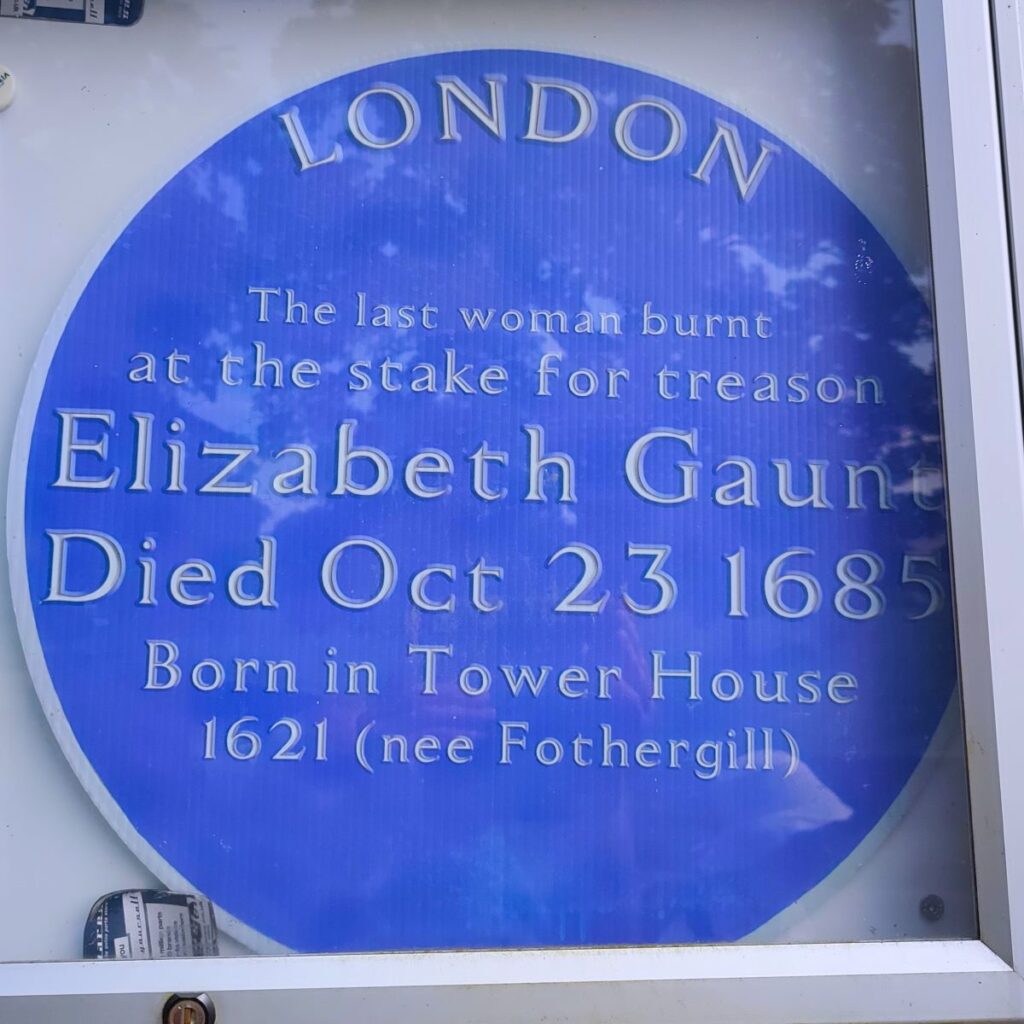

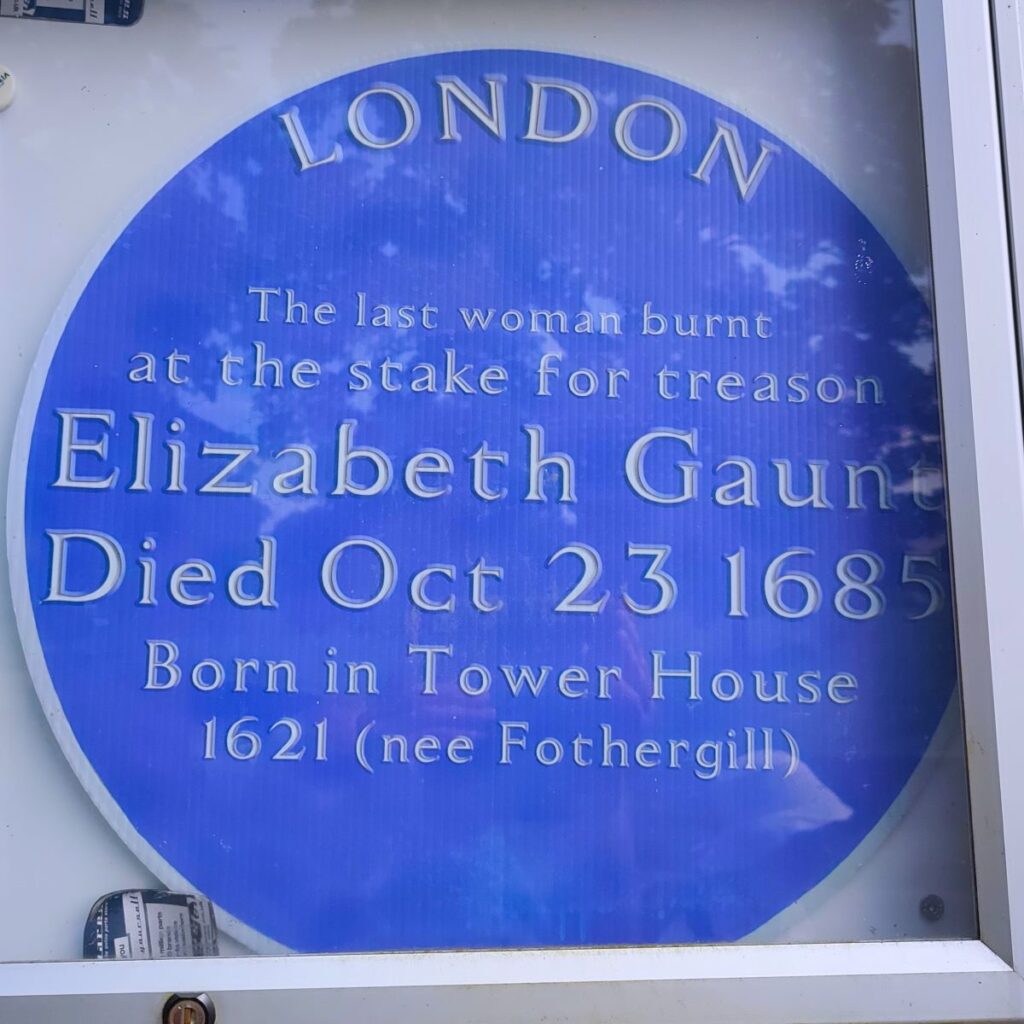

On the other side of the road is St Oswald’s church. The current church was built in 1738 to replace an earlier structure and retains a lot of the original Georgian interior- these are often lost when churches are modernised. Examples of this Georgian style within include a 3-tiered pulpit, and inward facing oak pews. Meanwhile, the chancel arch and south porch are retained from the earlier church giving a sense of continuity, and there is an unusual memorial window commemorating Elizabeth Gaunt a member of the longstanding local Fothergill family. More about her later in the walk.

Also within the grounds of the church are the remains of a small monastic house established by the Gilbertine Order. The Order was founded in about 1131 by Gilbert of Sempringham in Lincolnshire. It was the only English Monastic Order and had several establishments on the eastern side of England between East Anglia and Yorkshire. It included women as well as men but there is no evidence that there were ever nuns at Ravenstonedale. St Oswald’s is a Grade I listed building, and the medieval monastic remains are scheduled monuments.

We are now walking toward The Black Swan pub, but 50m before we get there, we take a small lane on the right signed to indicate that drivers should ignore satnav instructions to use this road. As we progress uphill, we see why – it gets continuously narrower. We follow the road until we arrive at a more open village green, and then continue onward.

This brings us to the edge of a farm where we follow the footpath indication and head right passing along the side of a farm building to a point where the path forks. We could go straight on, or as we do for this walk, head left and slightly downhill along a green lane with great views of the Howgills ahead of us.

After just 30m or so the lane comes to an end, and we head right into a field – the path is generally clear, and heads to the opposite corner where we pick up a track that heads slightly left and down to a bridge over a beck – we walked the route in the summer and found the beck to be absolutely bone dry, but there is clear visual evidence that it sees significant flow when in spate.

We cross the bridge and then head uphill, looking for a stile in the wall to our right just 20m ahead. This takes us into a field where we head west, keeping to the drystone wall at our left to avoid trampling the meadow. At this point we use the attractive farmhouse at Greenside as our landmark – and once we get to the field in front of it, follow the path round to the left and then through the yard to the minor road.

We turn left on the road and walk passing a curious sign warning us about mines. And then head slightly downhill toward High Greenside – there are a couple of cattlegrids on this section of the road, both with gated alternatives.

As the road starts to bear right and go downhill, we see a stile on the right which takes the path through fields at the back of the farm, then through a couple of hay meadows, eventually emerging at another minor road, at Will Hill.

Here we see an old lime kiln, a great place to sit and have a brew before continuing.

We head right on the minor road, and after just 100m or so cross a bridge over the beck to continue north past the farm. Don’t be too surprised if there is no evidence of water though, the name of this river is Dry Beck, so clearly there is an expectation that it is somewhat seasonal.

We continue north for 100m still on a fairly broad track. As it reaches a gate into a field we have a choice. There is a path to the right going through fields to Newbiggin-on-Lune, or a narrower route taking a more direct route to the village – we take this one, but if you miss it and accidentally take the other, it only adds a few metres to the route.

We initially walk through a quite overgrown and narrow section but soon emerge into open fields where we again stay to the left. Further over to the left we notice a body of water in the distance and in the centre of this is a large “fountain”. It is not an ornamental water feature of some grand house, rather it provides aeration for a trout farm at Bessy Beck.

A short while later the path emerges onto the road at Newbiggin-on-Lune, where we turn left, and almost immediately find ourselves in the centre of the village, with the old chapel directly in front of us.

Newbiggin is often cited as the source of the River Lune, a small cluster of springs, the most significant of which is known as St Helen’s Well (or Holy Well), are found on the northeastern edge of the village. It’s a good story, but modern geographers officially recognised the source as being Dale Gill and Stwarth Gill.

At the old Chapel we head right and walk down to the busy A685, which we cross with care.

Once on the far side of the road we continue up the track opposite. We are heading for Brownber next, and there is a clear track from the A685 to the village. This is clearly walked by thousands of people every year, but a glance at the OS map shows that the first 50m of the track is not a right of way, requiring you to walk up the minor road to the right for a while and then taking a public footpath back to the track. Those who feel the need to comply might take this more convoluted route – we took the obvious direct line.

We soon pass under a disused railway bridge – a clear indication that we are getting closer to the highlight of the walk, and then stroll uphill slightly to Brownber, where we meet the Tower House, a listed 17th century residence with initials T & FA prominent on an undated lintel. To the right of this is a pretty 19th century gateway and coal store, which has been converted into a very attractive courtyard.

The Tower House was the birthplace of Elizabeth Gaunt (nee Fothergill), famous as the last woman to be executed for a political crime in the UK.

Click here for a wikipedia article about Elizabeth Gaunt and here for one from bound-together.org

Gaunt was a member of the Anabaptists – a branch of the Baptists founded on the continent in the 16th century. They refused to have their children baptised on the basis that it was meaningless to baptise a person who had not formed their own commitment to the church, preferring the baptism of older believers, hence the word Anabaptists from the Greek, meaning re-baptisers – In today’s language, we might describe Elizabeth Gaunt as a born-again Christian.

Today we might see this as a minor issue, but Anabaptists were vigorously denounced by both Luther and Calvin and were severely persecuted by Roman Catholics and Protestants alike. The numbers put to death probably ran into tens of thousands.

Gaunt’s specific “crime” was not being an Anabaptist however, rather it was that she helped one of the participants of the failed Rye House Plot of 1683, James Burton, to escape to Amsterdam. After his arrest in 1685, Burton implicated her as an accomplice in the hope of saving his life. She was in fact not involved in the conspiracy and the trial against her is now seen as something of a show trial.

At Brownber we head right, and soon arrive at the obvious track bed of the disused railway. We take the path to the left and walk along the railbed for the next mile of so. This was once a thriving part of the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway (SD&LUR) railway line linking the Stockton and Darlington Railway near Bishop Auckland with the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway (which we now call the West Coast Main Line) at Tebay, via Barnard Castle, Stainmore Summit and Kirkby Stephen. The line opened in 1861 and became known as the Stainmore Line.

The line closed in stages between 1952 and 1962, although a short section of the line at Kirkby Stephen East station has been restored by the Stainmore Railway Company.

Like many disused railways, this now a great walk, and the embankments on either side of the track now provide a home for a profusion of wildflowers.

To the right there are great views across the valley to Smardale Bridge which we see later on our return route., and soon we meet the impressive Smardale lime kilns. Lime kilns are common in this area, and are often quite small, but the Smardale kilns are interesting in that they show a halfway step between the small local kilns providing lime for construction and agriculture at the point of use, and the vast industrial plants such as the Hoffman Kilns at Langcliffe. The Smardale Kilns were initially built to provide the lime for the viaduct which we meet next, but post construction they continued to operate using the railway as a commercial lifeline shipping lime further afield.

The twin kilns have recently benefited from restoration and stabilisation works and are home to a diverse flora and fauna including the common lizard – one of three species of lizard native to the UK. (The slow worm and the sand lizard complete the trio). Living up to its name, the common lizard is the UK’s most common and widespread reptile and is found across many habitats, including heathland, moorland, woodland and grassland, where it can be seen basking in sunny spots. Also known as the ‘viviparous lizard’, the common lizard is unusual among reptiles as it incubates its eggs inside its body and ‘gives birth’ to live young rather than laying eggs. Adults emerge from hibernation in spring, mating in April and May, and producing three to eleven young in July. The common lizard is quite variable in colour, but is most often brownish grey, often with rows of darker spots or stripes down the back and sides. Males have bright yellow or orange undersides with spots, while females have paler, plain bellies.

The lime kilns are a great place to pause for lunch, and to enjoy the wildlife – as well as the common lizard we saw Scotch Argos and (probably) common blue butterflies.

Pressing on, our next landmark, just 100 ahead is the Smardale Viaduct. The viaduct was designed by the Cumbrian engineer Sir Thomas Bouch on behalf of the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway, which served to carry coke to the iron and steel furnaces in the Barrow area and West Cumberland.

Click here for a wkipedia article about the railway, or here to visit Edenvaiducts.org

The viaduct runs across the Smardale Gill, and Scandal Beck, 27m high above the valley and was constructed of locally quarried sandstone featuring 14 arches of 10m span, over a total length of 170m.

It was built in 1861 by Mr Wrigg, a contractor from Preston at a cost of £11,298 – a number that equates to about £1.2 million now. The viaduct was wide enough for double track, but never carried more than a single line of rails. It closed after steelmaking finished and for many years the viaduct stood disused and deteriorating from lack of maintenance and exposure to the weather. British Rail intended to demolish it as it became dangerous when masonry fell from several of the piers, but Eden District Council stepped in and arranged for it to be listed. British Rail offered £230,000 (the estimated cost of demolition) towards its restoration if a charitable trust could be formed to raise the balance and accept ownership. The Northern Viaduct Trust was formed in 1989 with funds raised via grants from a number of organisations, including local authorities, the Countryside Commission and English Heritage.

In 1992 it was formally handed over to the Trust, together with the nearby Drygill Bridge, to become a permissive footpath. It is now listed Grade II* and has won a National Railway Heritage Award.

At the far side of the viaduct (which was undergoing some maintenance work at the time of our visit – hence the presence of so many vans in the picture), we see a stile leading to a permissive path down the far side of the valley on our right.

As we follow this pleasant path down through the trees we get great views of the viaduct on our right, and from this lower level can see the protruding stones at the top of the columns which were used to bed temporary wooden supports during the construction of the arches.

We soon arrive at a drystone wall where a gate gives access back to public footpaths, where we go right and continue downhill to the rather lovely Smardale Bridge – which like its rather larger neighbour crosses the wonderfully named Scandal Beck.

There are paths back to Ravenstonedale on both sides of the bridge – we took the one on the far side, which we accessed by crossing the bridge and then heading uphill for 20m or so to find the stile on our left. This leads to a path which we follow for a while using the left hand side of the woodland at the top of the rise as our landmark. At the edge of the woodland, we see a gate and follow the path along the bottom of the tree line for about 50m. We then continue along to another gate then clamber down the steep scar and approach Scandal Beck.

We cross a stile and almost immediately after, a small bridge, then climb up to a farm track. We are not on the track for long though – the footpath leaves on the left to head back down to the riverbank, which from here onward would best be described as pungent: There is a sewage treatment plant adjacent. Publicly available data shows that in 2020 this overflowed for more than 3000 hours. The extensive visible pollution of the beck in July 2024 suggests that little improvement has been made since.

We pass a curious “Dexion” bridge, and then walk under the main road to arrive back adjacent to the Kings Head, where the walk ends.

Did you like this walk? . . . Then try this one for a slight variation