Jump to . . .Step by Step | OS Map | Downloads | Gallery | Fly through

This excellent route showcases just what great walking country we have right on our doorstep. We start from Langcliffe, less than half an hour away from Bentham, and then fill the day with the kind of walking that you might see on one of those “celebrity buys some walking boots” TV shows.

We head out of Langcliffe on the Pennine Journey path, hop over to the Pennine Bridleway, and then take a footpath up to Victoria Cave, which we explore for a while before walking along the base of the wonderful Attermire Scar.

We follow that round, passing under the entrance to Horseshoe Cave, before heading over to Stockdale Lane with great views over to Pendle Hill, and Rye Loaf Hill. We then cut back along a footpath between High Hill and Sugar Loaf Hill to arrive at the base of the Warrendale Knotts. From here we retrace our outbound journey – although in this direction the views are surprisingly different -and then as a bonus treat, pop up to the smaller Jubilee Cave. The final part of the walk follows our outward route back to Langcliffe.

- Total distance 11.4 km (7.1 miles)

- Total ascent 592 m

- Easy walk

Step-by-Step

We start in Langcliffe, a small village just outside Settle on the B6479. There is parking available opposite the Church of St John the Evangelist – this operates on an honesty box principle. If you are using Satnav to get to the start of the walk, then the address is Main St, Langcliffe, BD24 9NF. The grid reference is SD82296508, or if you have access to a what-3-words device, use the tag shirt.plank.peach.

There are a number of other Bentham Footpath Group walks that start from here – or very near here – and Langcliffe has the advantage of being within walking distance of Settle, which makes this walk viable for public transport users.

From the car park, we head uphill on Main Street as if heading toward Malham. Before we go too far though, it’s worth taking a look at the rather beautiful church:

St John the Evangelist dates from 1851 and is one of the four ‘daughter’ churches of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick. The site, together with funds for the building of the church, was given by John Green Paley, a director of Bowling Iron Works at Bradford. He was a member of a prominent Langcliffe family which included Archdeacon Paley of Carlisle. The Bowling Iron Works was of national significance – you can read more about it by clicking here, and further details of the church and its stained glass windows can be found by clicking here.

As we leave the village, we are on the road for just a few metres, and we soon see a way marker on the right taking us out onto open fields. This is part of the Pennine Journey path which goes down into Settle, and if you look at the OS map, it appears that we need to walk some way down the Pennine journey toward Settle before we pick up the Pennine Bridleway to head North toward Victoria Caves. In practice this is not the case: Just stick to the drystone wall on the left as we climb steeply out of Langcliffe, and we soon find the Bridleway at the treeline – the prominent gateway pictured here is your landmark.

We now head North – away from Settle and left through the gate – to follow the bridleway along the base of the woodland and back to the Malham road. We join the road at a sharp bend. If you were driving uphill, the road goes left and ahead is a rough track – this is part of the Pennine Bridleway, and this is the route we take toward Victoria Cave.

We head up the lane passing a cattle grid, and then continue uphill with great views across the Ribble valley toward Gigglewick Scar and the quarries at Horton behind us. We soon arrive at this barn, and ahead we can see Attermire Scar looming, with Victoria Cave visible part way up. It would be tempting to assume that there is a path through the fields from this barn – there is not – carry on up the lane until the next gate, and just after this we see a fingerpost showing us the right of way to the cave.

From here, the path hugs the drystone wall as we head along the base of the scar. The entrance to the cave is via a small path that leaves the main path on the left – it’s a bit of a climb and can be slippery when wet so take care.

As we get higher, we notice a small cave entrance on the left – there are many caves in this area, and this is not Victoria Cave so press on for a while until a much larger cave entrance presents itself.

It is often said that Victoria Cave was discovered by chance – what this means in effect is that until relatively recently it was filled with mud and soil, and so not accessible. Archaeologists and “gentleman scientists” in the 19th century were of the strong belief that excavating ancient caves could reveal much about our evolutionary history so in 1837, the year of Queen Victoria’s coronation, excavation began.

Since then, it has been completely excavated and has yielded a fascinating record of climate change in the Yorkshire Dales over several millennia.

The cave was clearly used as a habitable site, as it contained numerous prehistoric bones. The earliest of these are dated at 130,000 years old and include those of hippos, rhinoceros, elephants and spotted hyenas. So clearly, they indicate a period in history when the local climate was much warmer than today – largely because this part of the earth’s surface has drifted North from balmier tropical climes.

Following the last Ice Age, the bone finds indicate that the cave was used by hibernating brown bears, and hunters who fashioned harpoons out of reindeer antlers – this is generally agreed to be the first definitive evidence of human habitation in what we now call the Yorkshire Dales.

For modern archaeologists, the Roman traces are even more interesting, giving up a collection of unusual bronze and bone artefacts. Finds include brooches, coins and pottery, some imported from as far away as France and Africa. Archaeologists have speculated for years as to what exactly was going on in the cave and it now seems likely that the inside was used as a shrine and there was a workshop area outside. For more detail about the caves, we recommend these links:

Prepare to be stunned by the 3D animated artifacts on the second link!

From the cave, we return to the path at the base of the scar and then head left. As we progress, we get great views over Sugar Loaf Hill toward Pendle Hill ahead, and the back of Warrendale Knotts to our right. To our left is Attermire Scar.

After a while the path starts to head downhill – we notice a gate in the drystone wall on our right – don’t be tempted to take this – it’s part of our return route. Instead, we carry on downhill, and follow the base of the scar round to the left, to walk underneath the Horseshoe Cave entrance, and then round to Stockdale Lane – a minor metalled road.

We join the road at a bend and need to head right (downhill) for a little while. It is worth noting here that if we were to head left, we would be joining the route of another of our walks: Langcliffe Scar Circular.

We follow Stockdale Lane for about 1000m, at which point the road takes a sharp left turn whilst we see a stile and way marker on the right taking us back toward Sugar Loaf Hill. This should be easy to find, but if you find yourself meeting the larger Settle to Malham road (High Hill Lane) at a T Junction, you have overshot a little and need to come back.

We now head gently uphill – the large hillside to our left is High Hill, and ahead and to the right is Sugar Loaf Hill – we are taking the valley between the two. We are now more than halfway round, and this is a good place to take a break – there is lime kiln over to the left – it’s a bit a scramble to climb up there but the views make it worthwhile, and there is a good supply of bench sized outcrops to sit on.

From here we see Sugar Loaf hill to our left – it’s the conical shape of the hill that gives it the curious name: Raw cane sugar was originally produced by a series of boiling and filtering processes, after which it needed to be converted from a thick syrup into the dry sugar that consumers prefer to use. To achieve this, the hot syrup was poured into an inverted conical mould, made of either brown earthenware or sheet iron with an internal treatment of slip or paint respectively. The moulds and by extension, the sugar they produced, were known as sugar loaves.

Each mould stood in its own collecting pot. Over the next few days most of the dark syrup and non-crystalline matter drained through a small hole in the bottom of the mould into the collecting pot, leaving a hollow coating of (whitish) sugar crystals. Whole sugar loaves were shipped to Europe, where rich consumers broke away pieces using special nibbling tongs – now very collectable curiosities.

Having enjoyed a brief rest we head left again and past Sugar Loaf Hill – feel free to climb it if you wish – ahead we see a drystone wall at the base of the Warrendale Knots – we head to that drystone wall where we find a gate at which we head right.

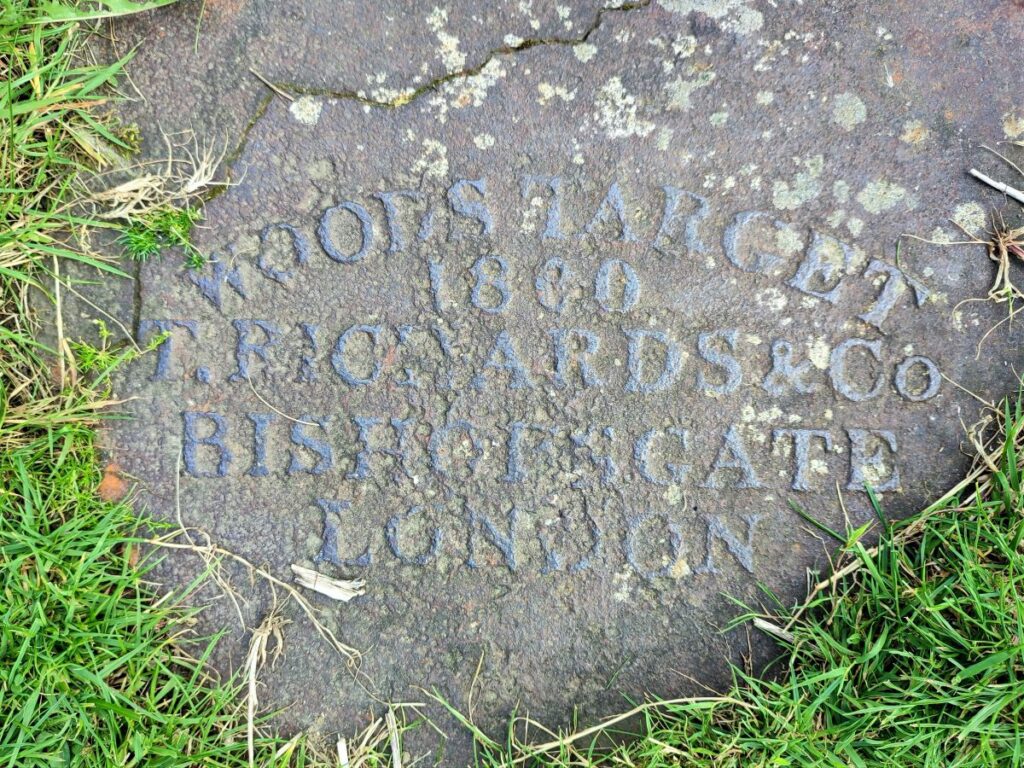

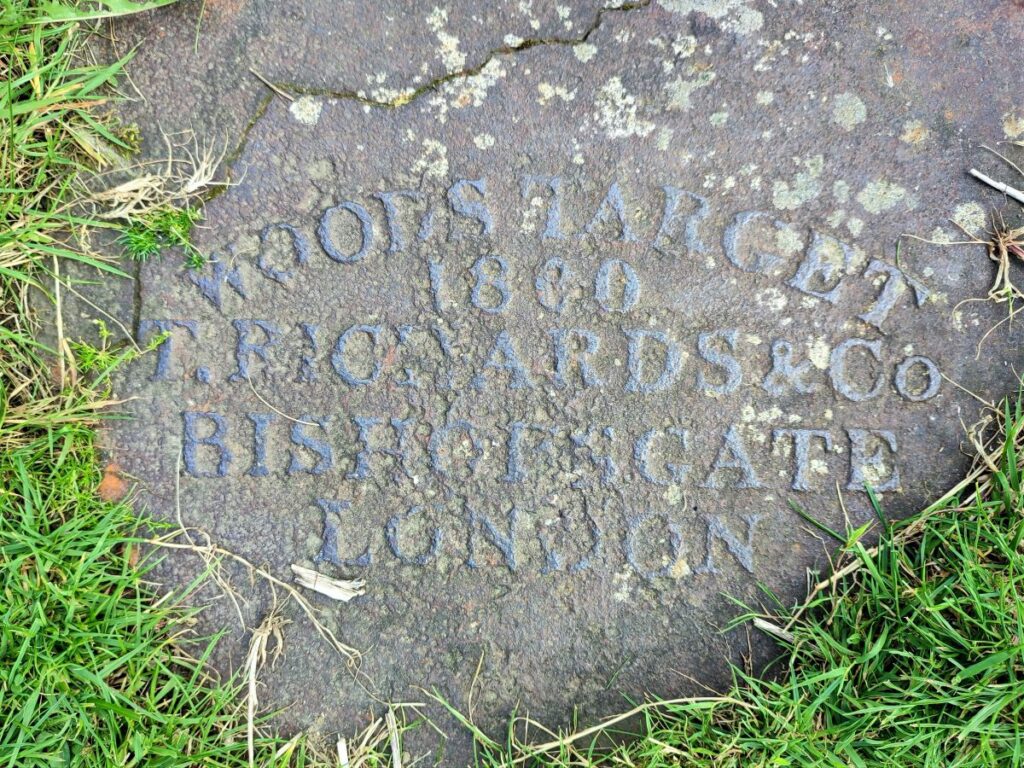

Our path now takes us downhill past a curious piece of local history: the remains of a shooting range. It is often assumed that this dates back to the second world war – in fact it is much older: In the mid-19th century, with the threat of war with France hanging in the air, County Lieutenants were tasked to raise volunteer rifle corps. This call to arms was taken up with enthusiasm – much like the volunteering at the start of the Great War, and so in 1854, 30 men signed up as the Settle Volunteers.

By 1864 they had a drill hall at the foot of Castlebergh in the town but needed a range on which to shoot, so in 1860, Attermire Range was set up for them. Competitions took place here and Settle won many of the top prizes in the county. The shooting platforms laid out at regular intervals away from the targets can only just be made out now. More obvious are the remains of the targets at the base of Warrendale Knotts half a mile away, which originally had pairs of two metre diameter targets.

The Settle Volunteers were transferred into the Territorial Army in 1908 and they continued to use the range up until and throughout the First World War. During the Second World War, the local Home Guard re-used the range.

Ahead of us, we see the drystone wall that we followed down from Victoria Cave earlier in the day, and halfway up we see the gate that we need to head for – then turn left to retrace our route past Victoria Cave and back to the lane that we left earlier in the morning.

When we get there it’s worth taking a short diversion to the right to find Jubilee Cave – this is about 100m up the lane and just to the right of the track. The cave is often considered to be part of the same system as Victoria Cave and has two side-by-side entrances with several subsidiary fissures appearing to connect with the interior. As for Victoria Cave, archaeological investigations have occurred since the late 19th century, and in addition to Iron Age and Roman materials, artefacts of Mesolithic and Late Palaeolithic eras have been reported from the cave. Although the cave itself has been investigated as far back as the blocked passageways, the areas around the cave mouth and the outside entrance platform contain considerable amounts of deposit which have been left undisturbed beneath a cover of excavation tip.

Having spent a while exploring the caves, we head back downhill. Simply retracing our outbound route until we reach Langcliffe, where if you have picked a Sunday for your walk, you can enjoy homemade cake and refreshments at the Langcliffe Village Institute.

To see some of the panorama shots we gathered during the walk click on the following links: