Jump to . . .Step by Step | OS Map | Downloads | Gallery | Fly through

The Ribblehead Viaduct is probably the most photographed railway bridge in the UK, and an icon of the Yorkshire Dales. It’s more than just a bridge though; surrounded by stunning countryside, and with traces of industrial archaeology dating back to its construction, there’s lots to see. So where better to start a walk?

From Ribblehead, we head under the viaduct and over to Gunnerfleet before following Winterscales Beck down to the intriguing Haws Gill Wheel where the river disappears and then reappears. After a very short section of road walk, we pause at the lovely St Leonards Church, before heading up to Ellerbeck, passing a sculpture as we go, and from there take the Dales Highway back to the railway. After a brief look at the Signal Box at Blea Moor, we return via the Viaduct with views over to Ingleborough and Simon Fell.

The Dales’ favourite railway, that bridge, a disappearing river, a beautiful church, art, and great views. What more could you ask for? A Xylophone . . . read on.

- Total distance 12.5 km (7.8 miles)

- Total ascent 206 m

- Moderate walk

Step-by-Step

We start at the Ribblehead Viaduct – there is roadside parking beyond the junction of the junction of the B6255 Ingleton to Hawes road and the B6479 to Settle. This is a prime location so if you intend to complete this walk in the summer holiday season, make sure you arrive early. We cleverly chose a wet day out of season to make the parking easier.

If you are using Satnav to get to the start, then the postcode for the railway station at Ribblehead is LA6 3AS, but don’t turn into the station, follow the road down hill to the junction and then on to the roadside parking. Alternatively use the What-3-Words tag remover.listening.torched, or OS Grid reference SD76597930.

The viaduct is immediately visible from the parking places, through it has to compete with Ingleborough to the left, and Whernside to the right for our attention. It’s tempting to just pull on the walking boots and dash over to see this magnificent bridge, but it’s worth pausing to note the information board close to the junction of the two B roads – during the summer months it may be hidden behind an ice cream van.

This gives some context for the industrial archaeology that surrounds the bridge: Construction started in 1869 and required a workforce of up to 2300 men, most involved in the actual building, but many at a brickworks built on site to provide construction material. The huge areas of temporary buildings that housed these men were serviced by a narrow gauge railway that carried materials to the site and waste away. Nothing remains of the wooden shacks now, but the routes of the narrow gauge railway lines are visible, as are infilled inspection pits that were used to service the railway stock during the build.

The picture here shows a trace of a railway bed to the left of the current footpath on our return journey.

The Ribblehead Viaduct carries the Settle–Carlisle railway across Batty Moss and so is sometimes known by the alternate name of Batty Moss Viaduct – in fact “Ribblehead” as a location is something of an invention – Victorian marketing in effect. When the station at the Southeastern end of the viaduct was built, it needed a name. There is no obvious town to reference, so the primary options were Batty Moss and Ingleton Road station. Theses were considered too mundane for such a magnificent location, so the Midland Railway coined the name Ribblehead. To be fair, the Ribble does rise nearby.

The viaduct is a Grade II* listed structure and is the longest and the third tallest structure on the Settle–Carlisle line. It was designed by John Sydney Crossley, chief engineer of the Midland Railway, who was responsible for the design and construction of all major structures along the line. The engineering prowess of the Midland Railway may have been exemplary, but their approach to Health and Safety however was typical of the time, and more than 100 men lost their lives during its construction. The fact that the number is uncertain speaks of the Victorian approach to the value of the humble labourer.

Fore more detail about the railway and the Viaduct, these sites are well worth visiting:

The path up to the viaduct from the parking is clear and well used – just before the viaduct it branches with a path heading uphill to the right of the railway line continuing to Whernside as part of the Three Peaks route. We take the track under the central arch and follow it along flat land to Gunnerfleet Farm, where we meet the Winterscales Beck for the first time. We cross and then follow the lane round to the left – initially along the right bank of the beck, although the lane soon moves away from the stream.

We stay on this track for a while now, generally heading Southwest, until we cross the Beck again at a simple bridge. 200 m beyond this the path leaves the track on the right and we follow it South, heading back toward to course of Winterscales Beck. If you miss this turn, the track ends up at the B6255, and although you could get back on track by walking right along the road, we would recommend turning back, so that you don’t miss the Haws Gill Wheel – our next landmark.

As Winterscales Beck comes down from the edge of Whernside, it grows as numerous smaller becks merge. However, a glance at the OS Map shows the river simply disappearing. So, what is happening here?

Also on the OS map here are the words Caves and Pot Hole – an important clue. This is Limestone country and over millennia water has carved routes through this soft and partially soluble rock to create caves and underground streams. The feature known as Haws Gill Wheel is part of this intriguing geology: The river disappears down a sink hole to reappear at a waterfall 20m south of its disappearance, and from here it tumbles down to another sink hole where it finally disappears to remain underground until it surfaces much further down the valley – we next see it at Chapel-le-Dale.

Under dry conditions, cavers gain access to Gatekirk Cave here – an explanation of the cave with pictures from the inside, along with an explanation of how the caves form can be found by clicking here.

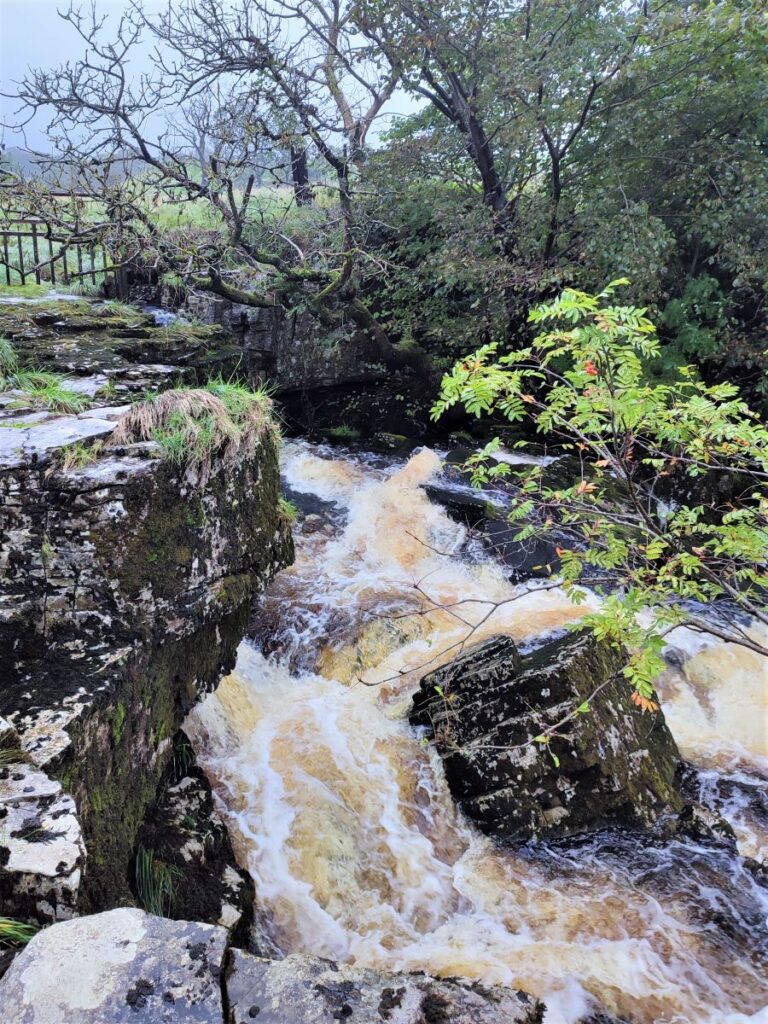

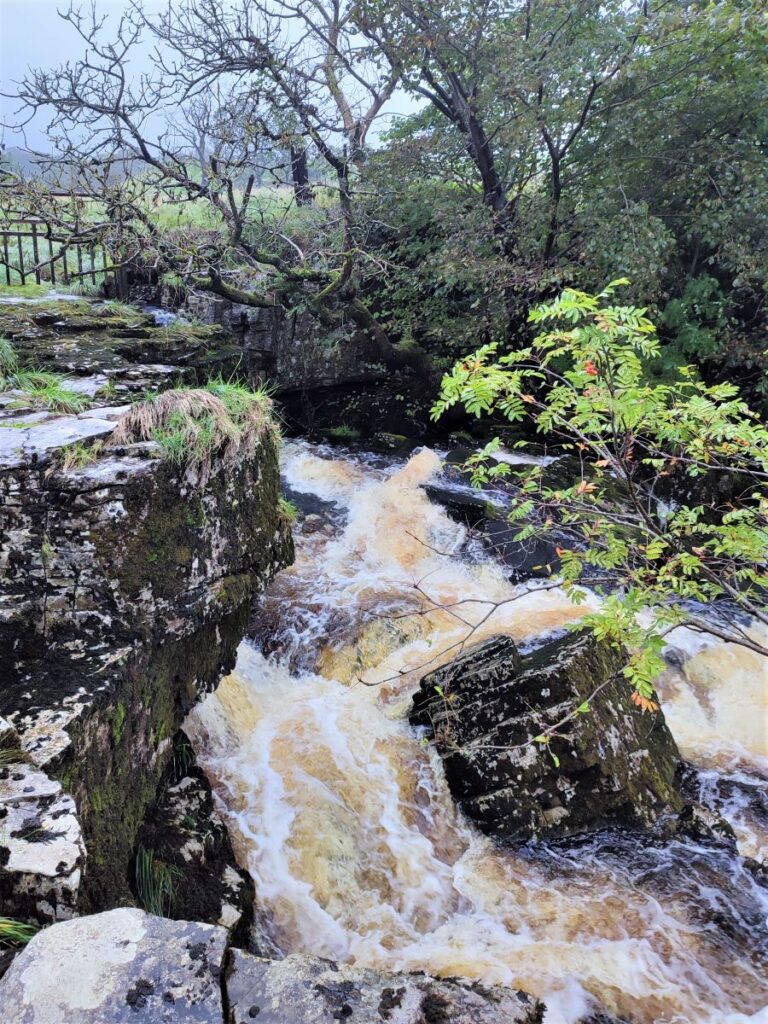

So why call the feature a “wheel”? That becomes clear when the river is in spate: The flow down the sink holes creates a bottle neck and a swirling eddy looking like a giant plug hole is created as the water wheels round. The contrast between the landscape in wet and dry conditions is enormous as shown in this YouTube video.

Our onward route has us cross the bottom end of the beck – not advisable under flood conditions – and then across a field to a gate where we walk along a dry riverbed to meet a farm track. At that track we turn left and head uphill past Philpin farm, and the excellent Philpin self-service snack bar, a welcome respite for many a Three Peaks walker. The lane eventually arrives at the B6255, where we head right walking downhill on the roadside for 400m. This is a busy road, so care is needed but visibility on this section is good – this is a Roman Road after all – and we soon arrive at the signpost showing us the road to Chapel-le-Dale, which is on the right.

The road to Chapel-le-Dale crosses the head of the river Doe (also known here as Chapel Beck) – which flows all the way down the valley into Ingleton where it merges with the Twiss to become the Greta. This is where the water that we saw disappearing at Haws Gill Wheel emerges – although there is debate as to whether all of it emerges here or just a part.

Beyond the stream we head up to the pretty church of St Leonards, which is famous for two things:

Firstly, as the burial site for the many men who lost their lives in the construction of the Ribblehead Viaduct. This is marked on a white marble memorial which reads: To the memory of those who through accidents lost their lives, in constructing the railway works, between Settle, and Dent head. This tablet was erected at the joint expense, of their fellow workmen and the Midland Railway Company 1869 to 1876

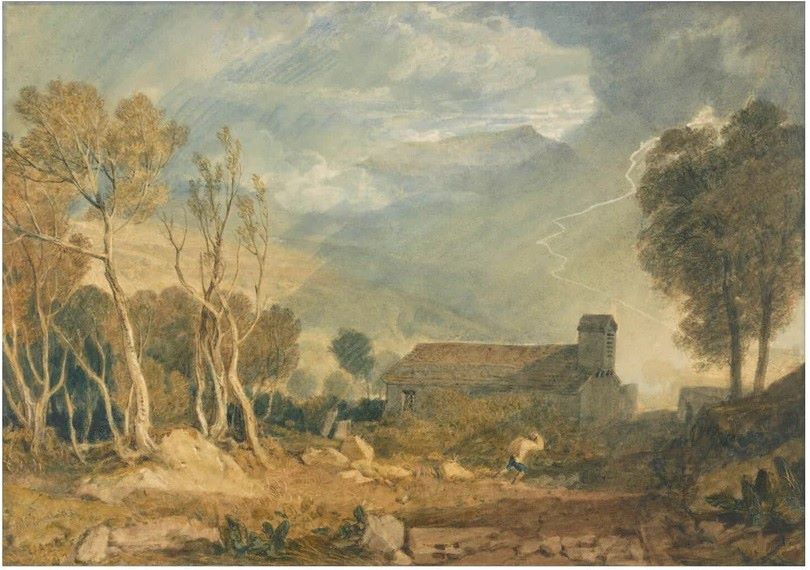

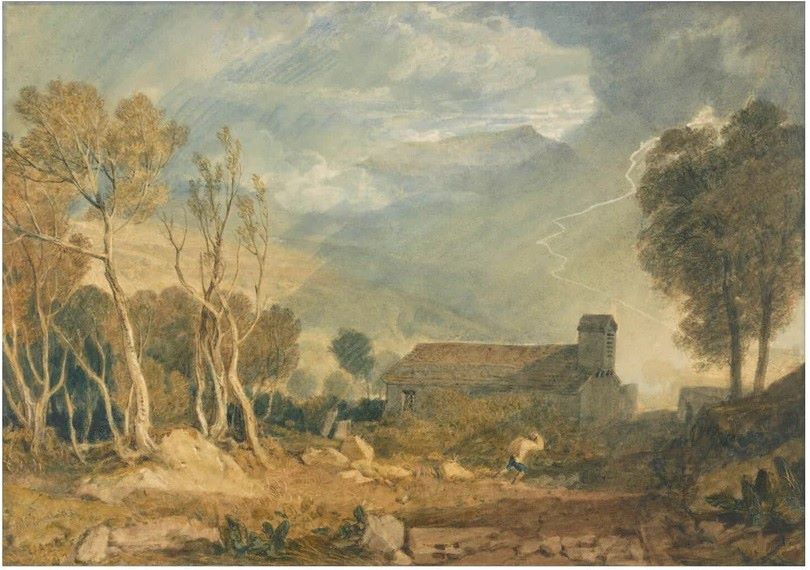

Secondly as a work of the Victorian artist JMW Turner, who combined the church with a view of Ingleborough which to be charitable, somewhat exaggerates the majesty of the hill and indeed revises the geography – as was typical in landscapes of the time.

Having spent a few moments admiring the church, we head up the lane to the side heading back toward the ridge of Whernside.

The climb is initially quite steep, and we walk through dense woodland with a wonderfully atmospheric mossy covering on all the rocks to the side of the track. We soon reach a statue on our left – this has an interesting history. The work was created by Charles I’Anson and is known as the Statue of a Warrior. It has stood at this location since the 1960s but was vandalised on Saturday August 27th, 1983, and subsequently found in 30 feet of water at the bottom of Hurtle Pot – just behind St Leonards. An enthusiastic team of divers managed a retrieval, and it has been re-erected, this time in a deep foundation.

We carry on up the track, and soon arrive at a broad plateau with the ridge of Whernside looming above us. We carry on up the track as far as the ford over the Ellerbeck where we meet the Dales Highway – and we head right along the bottom of Whernside on a well signed and generally easy track.

We press on along the Dales Highway passing a number of farms – the route is clear and well signposted at all of them. Highlights along the way are Bruntscar – a 17th century Grade II listed farmhouse, and just beyond this a limekiln where the path down from Whernside crosses ours. We need to continue Northeast on the flat track back toward the viaduct.

Our next landmark is Broadrake which combines a bunk barn with craft workshops – visit the Broadrake website to see the impressive range of options. Also of interest here is a fully functional stone xylophone at the picnic tables at the front of Broadrake – which we assume is linked to the workshops.

We soon pass Winterscales farm and follow the track up to a tunnel under the railway – we are now to the North of the viaduct at a place noted on the OS map as Blea Moor Sidings – although there is no sign of any rail line other than the main through line. At this point, we take a small detour to the left up to the signal box where the portal for the Blea Moor Tunnel can be seen.

From here we head back down the path at the side of the railway line, enjoying a different perspective of the viaduct, initially looking down on the line as it arcs round to Ribblehead station. At this point we have a good view of Ingleborough, Simon Fell and Park Fell to the right of the station. Also worth noting are the traces of the old narrow gauge tracks that serviced the construction site and temporary encampments for the navvies – look out for interpretation boards on the way back to the car parking.

This walk is just over 12km so we define it as “moderate” but those who favour our easy walks should note that there are no steep sections, and under dry conditions the paths are generally easy going (the short section of dry riverbed at Haw Gill Wheel is the only exception).