Jump to . . .Step by Step | OS Map | Downloads | Gallery | Fly through

Offering interesting walks on as frequent a basis as we do within the Bentham Footpath Group is a challenge. One which we compound for ourselves by trying to ensure that everything we do is new to the group. Every now and again though, we complete a walk that is so good we think it’s worth revisiting with a minor variation.

So, this is a slight reworking of our walk from 6th May 2022, taking a different route through the mine workings at Benfoot Brow. This simple change makes the walk sightly shorter and a little easier, making it more suitable for the shorter winter days.

It still includes the wonderful climb up the Dib, along with an alternate gentler route to the fantastic limestone pavement adjacent to the Bycliffe Road. We still walk the Conistone Turf Road, via Copplestone Gate to see the bleak spoil tips from past lead mining, before taking in Swinber Scar, Conistone Pie and St Mary’s church in Conistone. Take the GPS for both versions and you can decide which walk to follow as the day unfolds

- Total distance 11.1 km (6.9miles)

- Total Ascent 369 m

- Easy walk

Step-by-Step

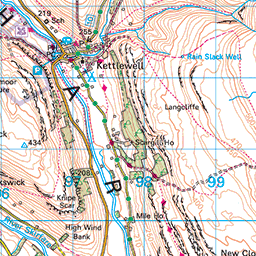

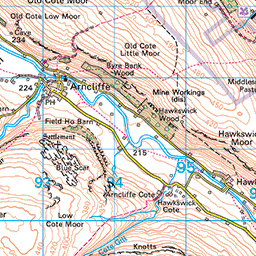

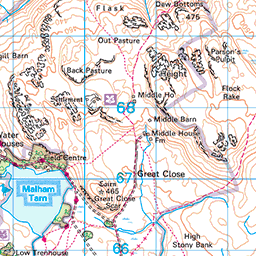

We start in Conistone, using roadside parking adjacent to the bridge over the River Wharf. Please park in a manner considerate to local residents, and make sure you leave room for large vehicles to access the stables. Conistone is just off the B6160 between Threshfield and Kettlewell and is well signposted. To find the start use grid reference SD97876750, or the rather splendid what-3-words tag satin.hamsters.dries. Satnav users should find that postcode BD23 5HS gets them to the bridge.

From the bridge we head East over the river, and slightly uphill into Conistone, passing the trekking centre on our left. From there we soon arrive at the very attractive centre of the village with the tall maypole ahead of us.

We take the left hand fork to pass the maypole and then almost immediately find a track on our right heading out toward the Dib. The Dib is believed to have formed as a glacial meltwater drainage channel during the last ice age and although it is now dry, it does feel very much like we are climbing up the route of a waterfall.

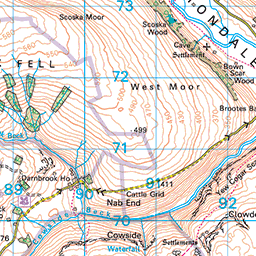

The path through the Dib eventually goes up to Grassington Moor and Mossdale Caverns – and although we do not go that far on this walk, those options are worth exploring another day, perhaps as part of our Yarnbury Lead Mines Walk.

The route through the Dib is clear but can be challenging – particularly in wet conditions, as some clambering over quite large stone steps is required. We are in the realm of tough walking here rather than rock climbing, but if a gentler route is required, rather than taking the first lane in Conistone take the road past the church and take a right up Scot Gate Lane until you find the Dales Way where the two alternatives come back together. We recommend the Dib as the primary route – the sense of adventure is better and the views back through the steep gorge are well worth the effort.

At the top of the Dib, we arrive at a flatter area where we find the Dales Way crossing our path. We briefly take this to the left through a wooden gate and head uphill to meet Scot Gate Lane – a wide green lane that eventually finds its way over to Mossdale. Scot Gate Lane is also the “easy” route up from Conistone, so if you opted to take that route, welcome back.

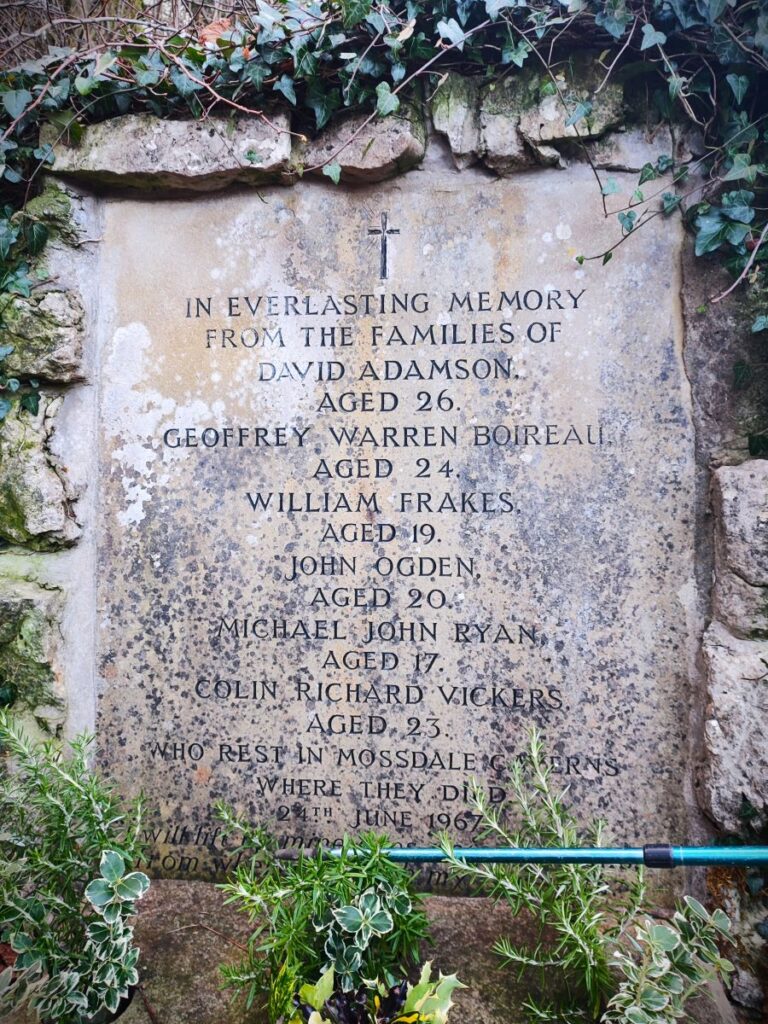

Mossdale is a name etched into the consciousness of UK cavers because of a tragedy that occurred on 24th June 1967. On that day, ten cavers entered the system. Three hours later, four members of the party decided not to continue and exited the cave. One of these four returned to the entrance a while later to find it completely submerged under the rapidly rising flow in the adjacent Mossdale Beck. Realising that the six colleagues who remained inside the cave system were in grave danger, she ran 4 kilometres across the moor to raise the alarm.

Cave rescue teams arrived at the scene, but the high water levels prevented access to the cave until the course of Mossdale Beck had been diverted away from the cave entrance by digging a trench. Even then, the rescue operation could not start immediately because of the high water levels inside. The following day, entry was possible: The cave rescue teams found the bodies of five of the cavers in the Far Marathon Crawls, a search party went to a location where they believed the sixth might have survived, but without success. The final body was located the next day. The deceased were left in situ, and the coroner instructed that the cave be sealed, with concrete being poured down the only safe entrance.

The entrance was later re-opened and in 1971, with the blessing of the bereaved families, the bodies were respectfully re-buried by their colleagues from the University of Leeds Speleological Association in “Mud Caverns”, a chamber at the far end of the system. This remains the most tragic incident in the history of British caving, and a stainless steel memorial plaque is fixed to the cliff above the entrance, and as we see later in the walk, a memorial at St Mary’s Church records the names of those lost.

To read more, click . . .

At the point where the Scot Gate Lane and Dib routes come together, we also find the Dales Way, which we use as a return route later in the day. Scot Gate Lane becomes Bycliffe Road at this point, and despite the names sounding like well-made tarmac roads, these are just rough green lanes and there is no traffic, other than the occasional horse to worry about. Our route is signposted for “Sandy Gate”, and we are now walking on much flatter land than at the start of the walk.

To read more about the Dales way, click . . .

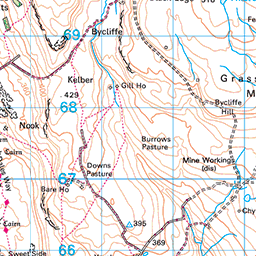

As Bycliffe Road heads up toward Conistone Moor, we pass through an area of really atmospheric limestone pavement – with gnarled hawthorn trees somehow finding a hold in the cracks in the limestone. To see this area at it’s best you need to make a point of looking back every now and again though. Over to our right there is a disused lime kiln, and according to the OS Map, but not particularly visible from our path, an ancient settlement site.

The Bycliffe Road continues on, and soon approaches a gate, beyond which it is enclosed between drystone walls. 200m later, we arrive at a crossroads where the route ahead becomes very overgrown. This is not a problem though because our route, signed for Copplestone Gate, leaves on the left. We are now on the Conistone Turf Road.

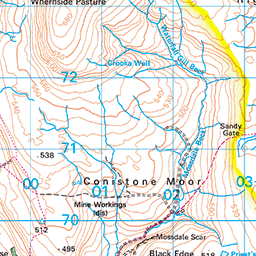

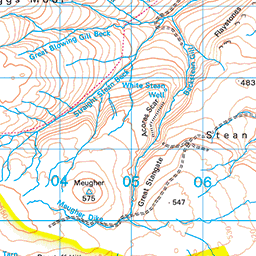

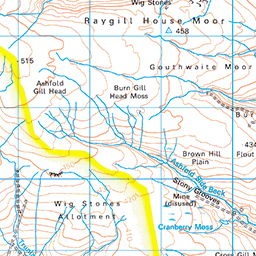

This heads North toward a stand of conifers where we find a gate leading onto Conistone Moor, where we follow round the edge of the trees to pick up a drystone wall which we follow up a steep hill. The path here is not particularly clear, and it may be easier to take a somewhat “alpine” approach to the climb. As long as you end up at the opposite corner of the field uphill from where you enter, everything will work out.

Ahead of us at this stage is a striking limestone scar – we need to crest this before we see the route continuing to climb, but now much more gently, toward Copplestone Gate, and a trig point at 512m.

On the way to the trig point we were lucky enough to see a rather unusual meteorological phenomenon known as a mist bow. This is similar to a rainbow, but rather than large droplets of rain diffracting the sun’s rays, it is tiny droplets of mist or fog that do so. This creates a bow that is predominantly white, with gentle hints of the usual rainbow colours running around the edges This rather beautiful phenomenon is also as a fog bow, or when seen from above when flying, a cloud bow, and when spotted by sailors in a sea mist, a seadog.

Find out more about this by clicking . . .

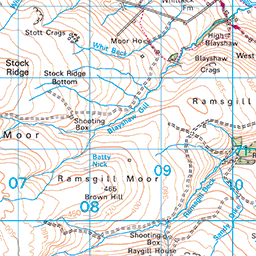

Just to the right of the Trig point is the Copplestone Gate – also known as Capplestone Gate. We take the gate and find ourselves on Conistone Moor, a large and rather bleak expanse of moorland that can be quite boggy after heavy rain, so if you want to explore off the main paths – take care.

We are now into an area that was once an important lead mining area, and the scars of this industrial activity are still clear. The mining was based on primitive “Bell Pits” where a shaft is sunk to reach the mineral, which is excavated by miners, and transported to the surface by a bucket attached to a winch, much like a well. These tiny bell pits would have been owned by single miners or their families. Once the ore – in this case Galena (lead II sulphide) – is reached, the bottom of the shaft is enlarged, and a domed roof is created as the desired mineral and surrounding rock is removed. This is where the reference to a bell comes from; the widening at the base means that in cross section the pit resembles a bell.

Typically, no supports were used, and mining continued outwards until the cavity was considered too dangerous – a stage often diagnosed only when it actually collapsed, at which point another mine was started, often in close proximity. The potential for the loss of life in this approach is obvious.

Such primitive bell pits also flooded due to a lack of a drainage system. This, together with the lack of physical support, meant they had a very limited lifespan before inevitably collapsing inward, and for this reason, none remain intact. The remains of bell pits can though be identified by depressions left when they collapsed. In some places, they will follow a straight line as the seam of mineral is being followed. Bell pits were not an efficient way of extracting minerals as they only partially exploited the resources, and for this reason were replaced by more effective techniques in later mines, although it would seem that no such further development occurred here.

Click here to learn more about lead mining in the Yorkshire Dales

The path through the lead mines is marked by a series of wooden stakes with yellow tops, and then as we get further into the spoil heaps, we see a distinct fingerpost. On our previous visit to this area, we headed up past the post and along the drystone wall at the top of the scar. Today however, we take the ladder stile in the wall (400m after the Copplestone Gate), to take a gentler route slightly downhill.

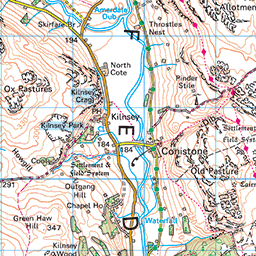

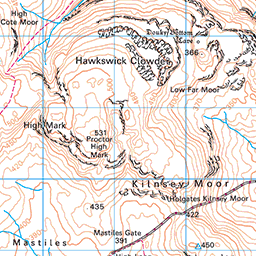

This takes us across a field, and then via another stile where we meet the path coming down from the scar which now looms above us. This is a good point to take a break and enjoy the views across the Wharfe valley to Kilnsey Moor and Crag.

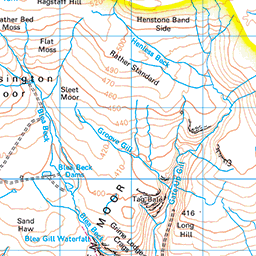

From here we head west, taking a clear and easy track down to woodland at Highgate Leys Lane, about 1km down the hill. This is where we meet the Dales Way again, and it would be easy to be tempted into the woodland and on to Kettlewell. That is indeed a good walk, but it’s not our route today, so we head sharp left (almost reversing our direction) to follow the contours around the base of Swineber Scar for 1500m.

As we continue along the Dales Way, we see Conistone Pie come into view. The Pie is a prominent limestone outcrop shaped, unsurprisingly given the name, reminiscent a stand-pie and it commands extensive views of both Littondale and Wharfedale which are divided by the Birks Fell ridge.

The view up Wharfedale extends as far up the valley as Buckden Pike and Yockenthwaite Moor. Down to the left meanwhile is a good view of another of Wharfedale’s finest limestone features – Kilnsey Crag.

The Dales Way path passes to the left of the Conistone Pie, but the pie is worth a moment or two to visit – on a clear day there are great views from the top. Once we leave the Pie though take care to use the stile on the Dales way – if you continue within the drystone wall, you will meet a dead end and need to reverse.

We stay with the Dales way for the next 500m until we meet Scot Gate Lane again. Just as on the way up, we have a choice of two routes, the lane or the Dib. Given that we used the Dib in the morning, and we were running out of light, we opted for the lane, turning right and heading downhill toward the radio mast.

After about 1000m this meets the minor road between Conistone and Kettlewell, where we head left. This brings us to St Mary’s Church, which was originally built in the 11th or 12th century. In 1846 the chancel was added and the nave and aisle were rebuilt under the supervision of the Lancaster architects Sharpe and Paley, who maintained its original Norman style of architecture. Another period of renovation was undertaken in the 1950s, which uncovered Saxon markings on undiscovered stones in the churchyard. This led to (unproven) speculation that the church could be the oldest building in Wharfedale, and possibly in Craven.

Of note within the grounds of St Mary’s, just to the left of the entrance gate is the memorial to those lost at Mossdale.

From the church we continue along the minor road to Conistone where the walk ends.

Bentham Footpath Group walks are classified according to length and elevation change. At less than 12km this walk is classified as easy – if you are choosing it specifically for this reason, we recommend the Scot Gate Lane route rather than the Dib.